-the cedar of Loughborough university

A Pandemic PhD Beginning

January 2021. I arrived at Loughborough while the world still held its breath during the COVID-19 lockdown. Four months later, my first experience of campus felt like a stage after the actors had left – library echoes, masked faces, and the physical weight of distance. My research on tribal oral traditions and storytelling, South India now faced a harsh irony: I couldn’t touch the soil I studied. Zoom screens replaced village circles. I questioned everything.

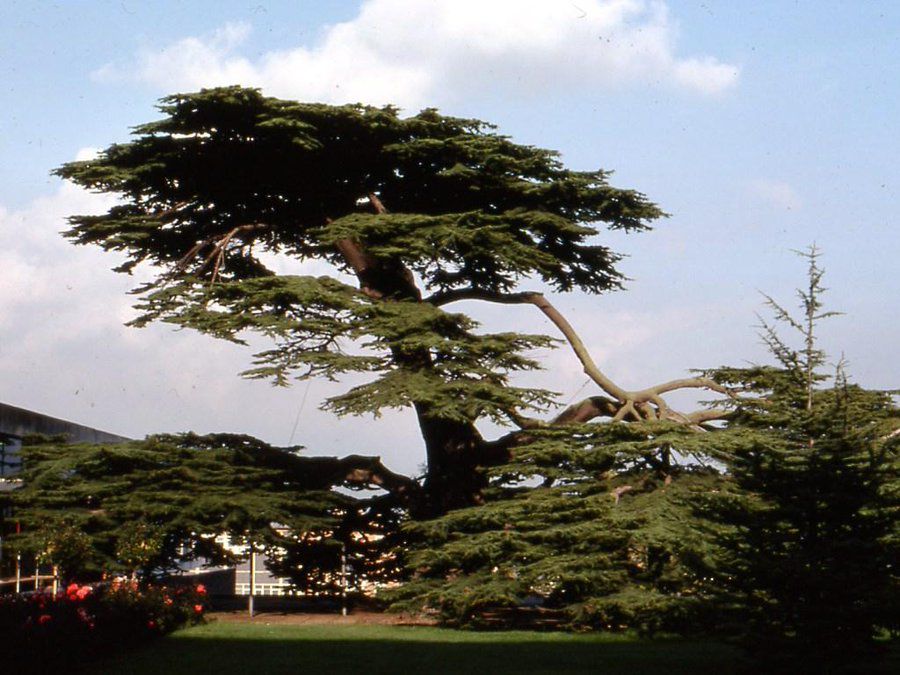

One rain-slicked afternoon, fleeing my fourth consecutive month in my room, I stumbled upon it: not my PhD student experience but the Cedar. A broken tree in the middle of an advanced campus made no sense. Why would they keep it? In fact, they preserve it! But why would they preserve it? Its branches, fractured, look completely odd and unique. I began visiting it, observing it.

A silhouette like a lightning bolt frozen mid-strike.

Limbs splintered, sheared off at cruel angles—yet braced by steel and oak crutches.

New growth exploding from the fractures, emerald against a storm-gray sky. That one defiant bough arcing upward—a against the mighty power of gravity.

This was no ornamental tree. This was a veteran. A 300-year-old immigrant from the Lebanese mountains, stranded in England’s chill. A survivor of blizzards and bulldozers. No courses taught its climate resilience. There are no dedicated programs to honor its service, and no widespread initiatives sharing the fascinating details of its life. I realized the cedar’s greatest threat wasn’t storms or disease – it was forgetting. In its silence, I heard a question: “What stories would this tree tell if it could speak?” So I have decided to tell the powerful story of the cedar at Loughborough University.

This archive isn’t an academic abstraction. It’s my pandemic survival manifesto – written in bark and in this digital code.

England’s Arboreal Legacy

England’s ancient trees stand as silent witnesses to millennia of cultural evolution, ecological adaptation, and human struggle. From the Norman Conquest’s harsh Forest Laws (c. 1070), which criminalised foraging in royal woodlands to assert control, to the Sherwood Forest oaks that anchor Robin Hood’s legend, trees have shaped England’s identity as symbols of power and resistance. These arboreal monuments—like the 2,000-year-old Ankerwycke Yew, which stood witness to the signing of the Magna Carta—encode history in their rings, merging myth with tangible heritage.

The UK’s woodlands also reflect ecological turning points. By 1919, deforestation had reduced forest cover to just 5.2%, leading to the creation of the Forestry Commission to rebuild timber reserves after World War I—a shift toward utility that often conflicted with biodiversity. Yet ancient survivors like Savernake Forest’s “Big Belly Oak” (over 1,000 years old) endured, becoming irreplaceable habitats and carbon stores. Today, initiatives such as the Ancient Tree Inventory use digital tools to protect these living relics from modern threats like Ash dieback and climate stress, echoing tribal practices of intergenerational stewardship.

Trees as Cultural Anchors and Resistance Symbols

England’s trees permeate its cultural consciousness—from Druidic veneration of oaks as gateways to ancestral worlds to Shakespeare’s Birnam Wood symbolising prophetic inevitability. Modern artists like Radiohead have drawn inspiration from ancient trees (The King of Limbs), while the atmosphere of Sycamore Gap in 2023 sparked national grief, revealing trees as vessels of collective memory. Campaigns such as Nature for Everyone now frame woodland access as a matter of social justice, challenging historical exclusion rooted in Norman-era privatisation.

This narrative reflects my research with the Yerukala, Irula, and Katru Nayakar communities of India, where trees are central to spiritual rites, healing practices, and performance traditions. Both contexts show trees not as passive resources but as active co-authors of human resilience, connecting ecological wisdom with cultural continuity in an era of ecological vulnerability.

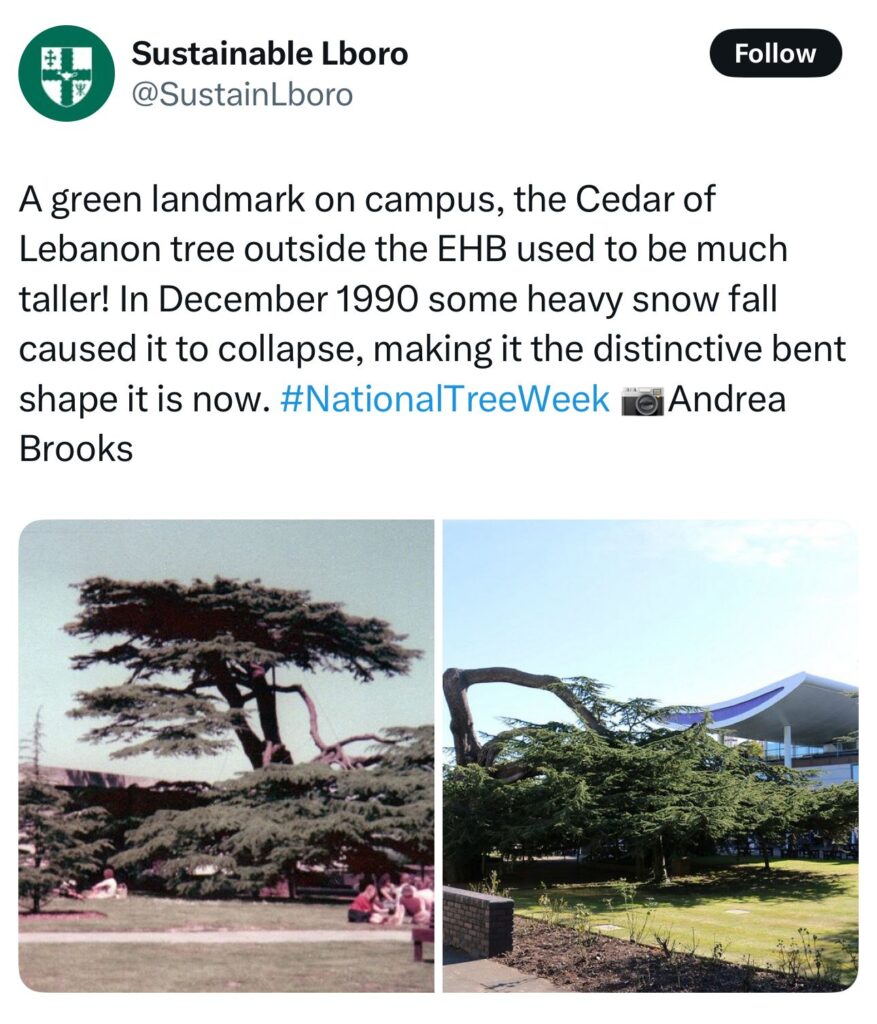

Yet at Loughborough University, the Cedar of Lebanon, once the living soul of campus life, now stands in muted isolation, carefully preserved. For over three decades after its fall in 1990, this arboreal elder has silently re-rooted itself in ecological space while fading from collective memory. This archive confronts that silence by igniting its digital rebirth: deploying immersive storytelling and spatial media tools to resurrect its layered narratives—from Georgian power symbol to its modern day silent whispers—and restore it as the university’s dynamic cultural compass.

The Cedar of Lebanon at Loughborough University: A Living Chronicle of Heritage, Resilience and Renewal

Arboreal Biography: From Aristocratic Symbol to Academic Heart (c. 1725–2025)

The first recorded Cedrus libani trees in Britain were planted at Chelsea Physic Garden around 1683, introduced by Dr. Edward Pococke and Dr. Leonard Plukenet from the Levant. By 1700–1725, the Cedar of Lebanon had become a fashionable status symbol among English and Scottish estates, especially favored by landscape designers such as Stephen Switzer and later Capability Brown. Among these historic Cedrus libani specimens stands the oldest living organism at Loughborough University, whose 300-year lifespan chronicles Britain’s social and ecological evolution.

The Cedrus libani at Loughborough University is a living tercentenary monument, offering a remarkable glimpse into the intersection of social, ecological, and architectural history embodied in a single living organism. Its life dates back to the Georgian era, reflecting significant transformations in the British landscape—from the formal gardens of the aristocracy to the modern academic environment. Originally planted as a focal point in the Baroque gardens of Burleigh Hall, the cedar symbolized the Tate family’s prestige and authority in the 18th century. Estate maps from that time emphasise the tree’s strategic location at the end of a carefully crafted vista, visible from the Great Room of the Hall, underscoring the family’s control over the surrounding estate (Willoughby et al., 2007).

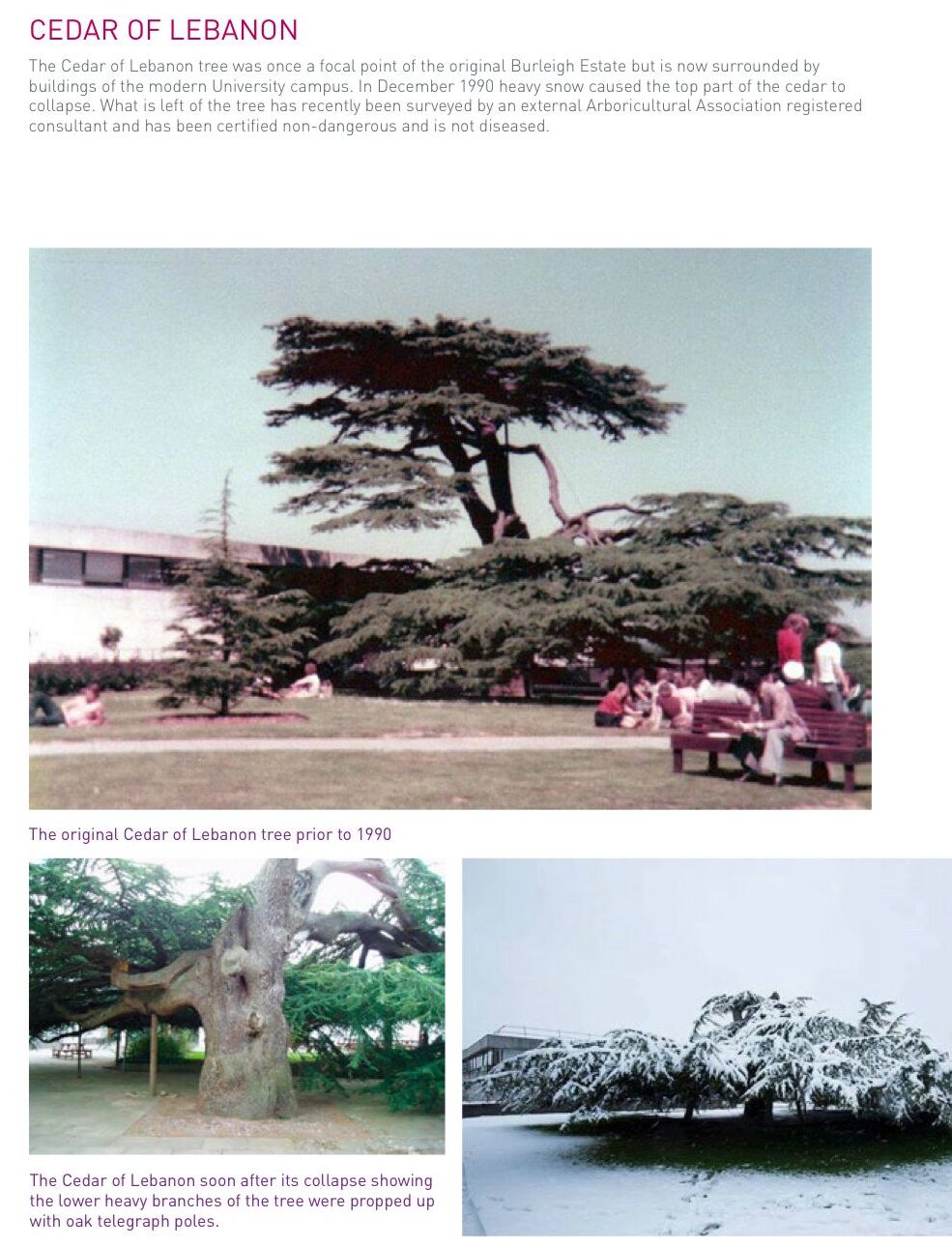

The tree has witnessed centuries of profound change, from the Industrial Revolution to the pollution caused by Loughborough’s hosiery factories in the 19th century. Dendrochronological analysis of its growth rings could reveal periods of slowed growth linked to spikes in industrial activity, providing concrete evidence of environmental impact on this living witness. Yet, the cedar’s story is not just one of survival but also of resilience, adaptation, and integration within a transforming landscape. Its preservation during the demolition of Burleigh Hall in 1958 was a visionary decision by the architects designing the new university campus. This was more than an aesthetic choice; it was a deliberate effort to unite history with the present, giving the academic institution a profound sense of continuity. Rather than succumbing to the post-war modernist trend of concrete and steel, the architects recognized the timeless value of this ancient tree, making it the natural centerpiece of the campus quadrangle.

Its survival defied post-war Britain’s push toward stark modernist austerity, becoming the spiritual heart between the Edward Herbert Building and the Herbert Manzoni Building. The cedar stands as a symbol linking disciplines and generations of scholars. Its enduring presence continually reminds the university of its roots, connecting the modern academic environment to the historic landscape from which it emerged. As a living testament to the deep relationship between nature and human history, it offers unique insight into the evolution of British society, technology, and architectural innovation.

The cultural significance of Cedrus libani reaches far beyond its striking appearance, embodying a rich history of social interactions and pivotal events that have unfolded beneath its branches for centuries. In the 18th century, the tree was a stage for displays of aristocratic power, with steward diaries recounting magistrates conducting land negotiations in its shade, using its low-hanging branches as natural seating. For instance, Winston Churchill’s well-known practice of holding cabinet meetings under cedar trees at Chequers draws a fascinating parallel, suggesting that the Loughborough cedar may have served a similar social and political role within its own historical context.

The Cedrus libani, like other species in its genus, exhibits remarkable genetic diversity that enables it to adapt and thrive in changing environmental conditions (Terrab et al., 2006). It also highlights the importance of preserving natural heritage within urban settings, ensuring that future generations can enjoy the ecological, social, and cultural benefits these trees offer. Campus forests, such as these, play a vital role in supporting students’ psychological well-being (Kim et al., 2021). The Cedar of Lebanon at Loughborough University stands as a living link to the past, a symbol of resilience amid change, and a dynamic hub of academic life. Restoration efforts, particularly in the face of climate change, may encounter challenges due to environmental constraints (Shackley, 2004).

Beyond its national importance, the Cedar of Lebanon holds significant cultural value in regions where it is cultivated. Its distinctive architectural form, marked by a broad, spreading crown and robust trunk, has inspired artists, architects, and designers for centuries. Renowned for its durable and aromatic wood, it has been widely used in constructing buildings, furniture, and various artifacts. Cedrus libani represents a vital reservoir of genetic diversity, making the identification of genetically distinct populations essential for effective conservation efforts. It is well-suited for integration into urban and suburban landscapes due to its landscape and environmental adaptability (Chaney, 1993). Notably, it demonstrates strong tolerance to frost and drought, enhancing its ecological and economic value (Güney et al., 2016). This resilience makes it particularly valuable for afforestation projects in areas facing climate change challenges and water scarcity. Ecologically, the Cedar of Lebanon ranks among Lebanon’s most valued forest species, assessed by economic importance, ecological contributions, and vulnerability. Despite stringent conservation measures, the forest continues to experience significant and ongoing decline.

The story of the Cedar of Lebanon at Loughborough University is one of profound transformation, evolving from a symbol of aristocratic power into a vibrant center of student life and academic pursuit until about thirty years ago. Graduation photos from the 1980s often show proud graduates standing beside the cedar’s trunk, diplomas raised high, embodying achievement and hope. The cedar stood tall and sprawling for generations, a silent guardian witnessing the rhythms of student life: laughter and worry, exams and farewells. It was there long before any of us arrived, and it seemed destined to remain long after we were gone. People passed beneath its shade without a thought or sat quietly beneath it to breathe, reflect, or even shed tears. Yet, despite decades of quiet service, what remains most vivid in memory—and what people still speak of—is the night the cedar fell.

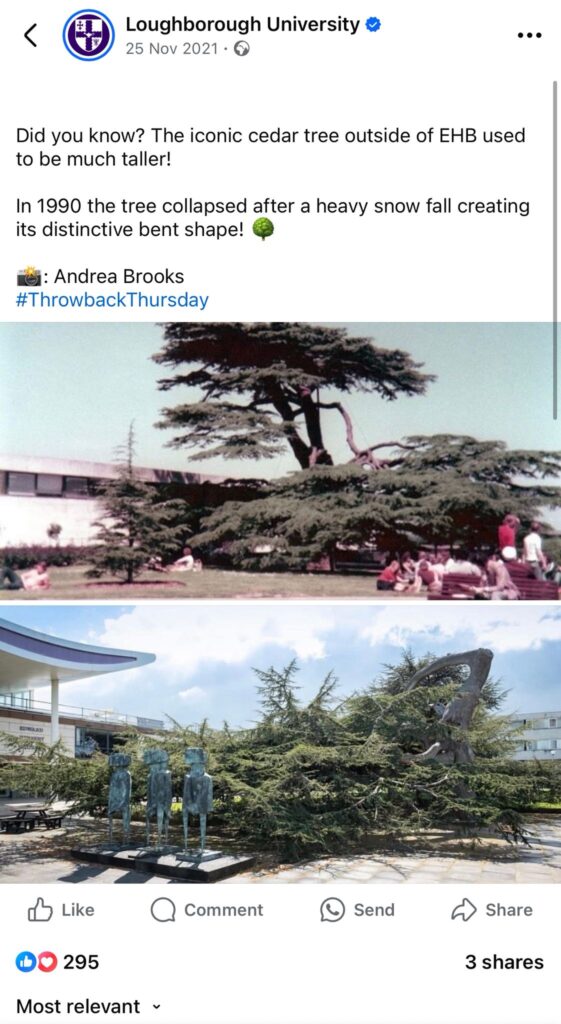

The Night the Cedar Fell – December 1990

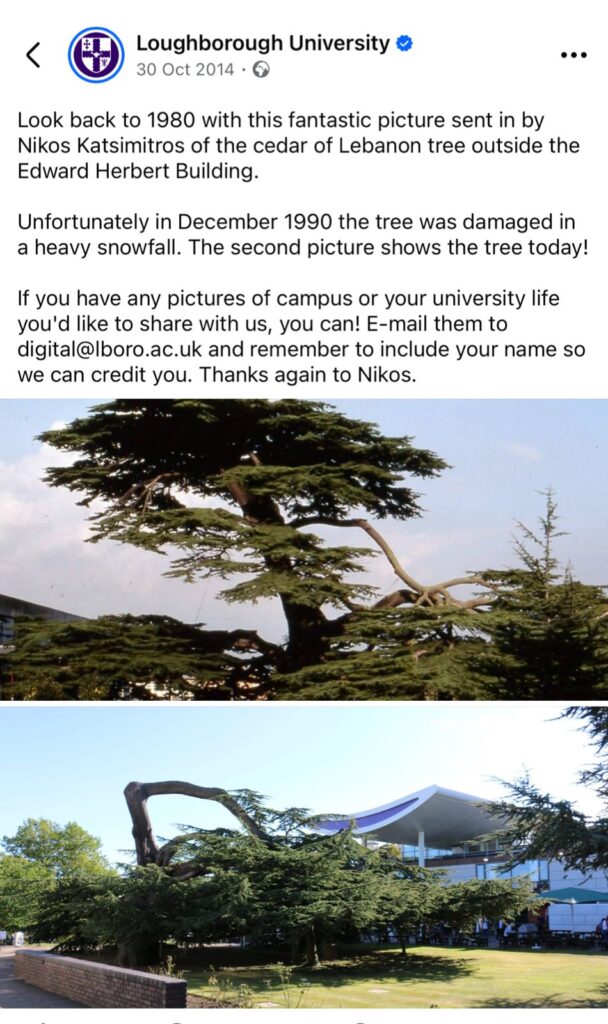

8 December 1990. The snow fell hard and fast, relentless, blanketing the Midlands in a fierce storm. It was as if nature itself had turned against its own. By morning, 43 centimetres had piled up—a snowfall so rare it only comes once in a lifetime. For three full days, there was no power on campus. No lights. No heating. Only cold, silence, and that tree—splintered beneath the impossible weight of over two tonnes of snow. The branches cracked like bones. Its shape was lost, as if time itself had bowed it, humbled it.

“Campus Giant Felled – But Not Defeated.”

Yet even in that moment of collapse, something remarkable emerged. Students—cold, tired, but determined—formed human chains. They dug the snow from around its limbs with bare hands and borrowed shovels. Others trudged through the snow just to see it, like visiting an old friend in pain. Because they all knew they cherished every moment of their student experience beneath it.

Now, whenever someone posts an old photo of the cedar online—on Facebook, Twitter, or a forgotten alumni forum—hundreds of comments flood in. People who haven’t spoken in years will say, “I remember that night. I remember the silence when we realised it had cracked.” Others recall the blackout—how they cooked by torchlight, slept in coats, and wrapped scarves around their faces inside their flats. But always, always, they talk about the tree. It’s like the moment it broke became a shared memory that no one can forget. A moment that stitched us all together with something deeper than just snow or silence.

The irony, of course, is that the cedar lived on. Bent, but breathing. Its limbs were braced with oak, its roots held steady. It still stands today, different—but still magnificent. Yet, it is not the years of strength that made people fall in love with it. It was the moment of its falling, and everything we saw in ourselves through it: vulnerability, resilience, grace. That’s why we still talk about it. That’s why it matters. The tree didn’t just survive a storm. It became a story—one that hundreds, maybe thousands, still carry with them. And in that sense, it never truly fell at all.

Veteran Status and Ecological Stewardship

Loughborough University has taken significant and multi-dimensional initiatives to protect and celebrate the Cedar of Lebanon, recognising it not only as a historic landmark but as an ecological and pedagogical asset. In 2021, sophisticated radar tomography scans were conducted on the Cedar of Lebanon at Loughborough. These scans revealed that the tree maintained an impressive 82% wood density—a hallmark of vitality—qualifying it under the UK Biodiversity Action Plan standards as a Category A veteran tree, a designation reserved for specimens with exceptional ecological and historical value. This level of internal integrity, despite centuries of life and structural trauma, speaks to its resilience and enduring presence on campus.

One of the more remarkable discoveries came from soil analysis: the Cedar’s mycorrhizal fungi network extends at least 60 metres beyond its drip line, forming a vast underground web that supports not just the tree itself but a host of soil organisms. This fungal alliance showcases its intrinsic ecological connectivity, anchoring the tree as a keystone species within the campus biome

Under the 2023 Green Flag Management Plan, the university implemented strict preservation protocols to prevent soil compaction around the tree’s vulnerable surface root system. Arboricultural reports now inform every campus development project near the cedar, ensuring construction is rerouted or adapted to its biological needs.

Cedar of Belonging: A Beacon for the Displaced

For many international students, immigrants, and asylum seekers navigating life at Loughborough, the Cedar of Lebanon is more than a tree — it becomes a quiet comrade in the long journey of becoming. Planted centuries ago on foreign soil, surviving storms, neglect, and the erosion of time, the cedar mirrors our own stories: uprooted, transplanted, yet fiercely rooted in new ground. In its patient, unmoving presence, it teaches us to endure — not passively, but with purpose. It tells us we don’t have to erase where we come from to grow where we are (Boyd, F. 2022).

That’s why #CedarWhispers is more than just a hashtag. It is a living archive of resistance and renewal — a sanctuary where voices too often silenced embed their stories into digital bark. Tales of migration, resilience in the face of the unknown, and the reimagining of home — all intertwined within a shared canopy of memory. I envision storytelling workshops blossoming beneath its branches: spaces where refugee poets, first-generation scholars, and those awaiting uncertain futures come together to share, heal, and be recognised. Through these gatherings, the cedar becomes more than a witness — it transforms into a partner, grounding our words in something deeper and stronger than fear.

Soon, I will walk across campus for the last time as a student. My PhD degree at Loughborough University—earned in another language, on unfamiliar soil, against many odds — will be clutched in my hand. But before I go, I will return to my silent teacher. I will stand before the Cedar of Lebanon, lift my head high, and say: “Thank you for standing. You taught me how to do the same.”

Note:- “Don’t forget to come back in December 2025 to see my graduation photo with this Cedar.”

#CedarWhispers

Blogpost

If this magnificent entity existed today, this is exactly how it would appear to us. Using the advanced capabilities of OpenAI, I was able to faithfully recreate the striking likeness of the majestic cedar tree in vivid detail.

References:

Willoughby, I., Stokes, V., Poole, E. J., White, J., & Hodge, S. J. (2007). The potential of 44 native and non-native tree species for woodland creation on a range of contrasting sites in lowland Britain. Forestry An International Journal of Forest Research, 80(5), 531. https://doi.org/10.1093/forestry/cpm034

Terrab, A., Paun, O., Talavera, S., Tremetsberger, K., Arista, M., & Stuessy, T. F. (2006). Genetic diversity and population structure in natural populations of Moroccan Atlas cedar (Cedrus atlantica; Pinaceae) determined with cpSSR markers. American Journal of Botany, 93(9), 1274. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.93.9.1274

Kim, J.-G., Jeon, J. Y., & Shin, W.-S. (2021). The Influence of Forest Activities in a University Campus Forest on Student’s Psychological Effects. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2457. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052457

Shackley, M. (2004). Managing the Cedars of Lebanon: Botanical Gardens or Living Forests? Current Issues in Tourism, 7, 417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500408667995

Chaney, W. R. (1993). Cedrus libani, Cedar of Lebanon. https://agris.fao.org/agris-search/search.do?recordID=US9403077

Güney, A., Zimmermann, R., Krupp, A., & Haas, K. (2016). Needle characteristics of Lebanon cedar (Cedrus libani A.Rich.): degradation of epicuticular waxes and decrease of photosynthetic rates with increasing needle age. TURKISH JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY, 40, 386. https://doi.org/10.3906/tar-1507-63

Boyd, F. (2022). Between the Library and Lectures: How Can Nature Be Integrated Into University Infrastructure to Improve Students’ Mental Health. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.865422

Leave a Reply